There's an apocryphal story that the Inuit languages of the Artic have at least 50 word combinations for different varieties of snow. Apparently young Inuit children learn those words and attach them accurately to the many varieties of snow simply by hearing them used in context.

Whether this is actually true or not, all children learn to correctly use the words they hear in their culture and family.

So when parents in any culture talk about a wide range of emotions, children learn to understand their own emotions and those of other people. Understanding and accepting emotions is the first step in learning to regulate them.

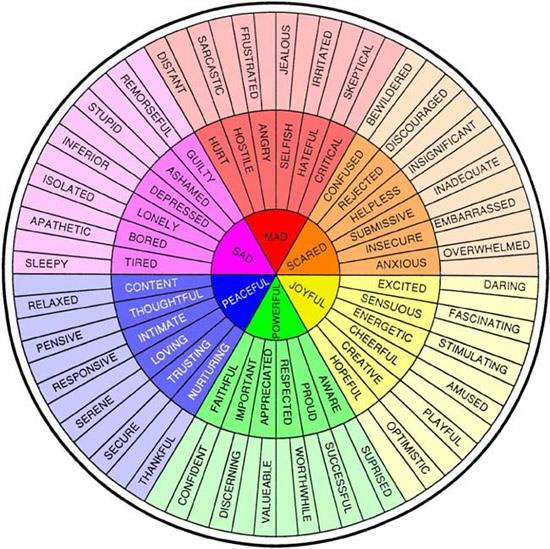

If you're wondering how there could be 50 different emotions, you'll be interested in the Feelings Wheel, invented by Dr. Gloria Willcox, which colorfully illustrates the wealth of emotions available to us.

But don’t worry if you find the idea of so many emotions overwhelming. You can simplify things by talking about just four basic emotions, going deeper as your child is ready:

Happiness, which includes love, joy, and peace. This is our natural state, when we’re in flow.

Fear, which is a reaction to threat and includes terror, anxiety (fear of an unspecified threat), worry (fear of a specific threat) and the feeling of being powerless or defenseless. Note that when mammals feel fear, they often shift into anger as a defense.

Sadness, which is a reaction to loss and disappointment, and includes grief, depression and loneliness. Note that many people defend against disappointment and sadness by becoming angry.

Anger, which is a reaction to threat from within or without and includes irritation, frustration and rage. Note that when anger is not heard, the person may turn it inward so that it becomes depression or numbness.

How can you teach your child about emotions? Simply observing what your child and other people are feeling, and commenting on it in a nonjudgmental, accepting way, teaches children to identify emotions in themselves and others. As you go through your day, look for opportunities to acknowledge your child's feelings:

- "You look frustrated.”

- “You're jumping up and down! You must be excited!”

- “I understand. You feel safer when you know exactly what's going to happen. Me, too.”

- “I hear you! You really don't like spinach and you wish you could never see it again!”

When you talk with your child about emotions, try to resist lecturing. Instead, ask questions to help him learn through reflection. For instance, you might ask questions like:

- "If you felt angry at a friend, what could you do?

- "If you felt angry at me, what could you do?

- "If you felt angry that your block tower fell down, what could you do?"

- "Do you make a better decision when you feel angry, or when you feel calm?"

- "What helps you calm down when you’re angry?"

If you and your child observe another child crying, you might ask questions like:

- “That child looks so unhappy. I wonder why he’s upset?”

- “What do you think he wants/needs?”

- “Is there anything we can do to help?”

Questions like these help develop empathy. For instance, when parents wonder aloud to their young child about what their baby sibling thinks, feel and wants, the child develops more empathy for their sibling and the relationship between the two siblings is more positive.

Reading books about children feeling and expressing emotions is another way to teach emotional literacy. Research shows that when adults read books and talk to toddlers and preschoolers about how other children feel, their prosocial (positive) actions toward their peers increase, and their aggression toward their peers decreases.

So the good news is that when parents consider emotion part of a rich human life, and talk about emotions in positive ways, even young children can learn to recognize and articulate a wide range of emotions -- sort of like Inuit children learning words for different types of snow. The even better news is that while naming snow doesn't tame it, when your child begins talking about their emotions, they're taking the first step in learning to manage their behavior.